Today I had an amazing professional experience. A client, who back in September suffered a hip injury, is now able to run again after a single session. Here's what happened...

Training was going well. We'd progressed from ~15 miles per week to about 23-25 miles per week over the course of 12 weeks and the only "speed work" was a series of 6-8 accelerations lasting about 100m. In other words, her training was very reasonable and didn't point to the trigger of her pain.

Today I had an amazing professional experience. A client, who back in September suffered a hip injury, is now able to run again after a single session. Here's what happened...

Training was going well. We'd progressed from ~15 miles per week to about 23-25 miles per week over the course of 12 weeks and the only "speed work" was a series of 6-8 accelerations lasting about 100m. In other words, her training was very reasonable and didn't point to the trigger of her pain.

She reported feeling very lethargic in tw0 consecutive runs ("really dragging"). Then on day 3, halfway through her run, her left hip suddenly became very painful. Type-A that she is, she finished the four mile run.

After limping around work all day, she tried foam rolling the site of pain, but the pain persisted. It now hurt when walking up stairs, too.

Still just thinking it would go away with rest, she wisely took a week off from running and got new shoes, optimistic that would help. Sadly, in her first run back, she only made it half a mile before the debilitating pain struck again.

I was on holiday in Africa at the time when she reached out for guidance. She felt guilty about emailing me while I was on vacation, but I assured her she did the right thing and I immediately referred her to the doctor.

She wasn't thrilled with the ('dismissive') evaluation she received but I was relieved to hear red flags (i.e., a stress fracture, tear, tumor, etc) were ruled out.

Finally, in mid-October our schedules aligned and we met for a session. She hadn't attempted a run and reported symptoms were still present. Not surprisingly, she was pretty down.

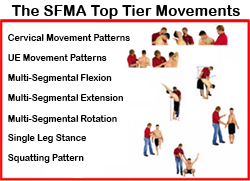

Movement screening showed a limited ability to extend her spine and hips while standing and her 'multi-segmental' rotation was restricted.

Neurokinetic Therapy® testing revealed a lack of function of several muscles around the core and hips. In my experience, this is very consistent with someone who's dealing with aches or pains. As a trainer, I cannot diagnose or treat pain, but I am going to look for non-painful movement problems.

With several spine stabilizers not functioning, the body often tries to compensate by either tightening other muscles or compressing joints. But that compensation won't usually hold up very well to the stress of training.

Clearly her body was sending out the bat signal for something - and it wasn't more physical activity. Think of it this way: If your brain considers it safe to move freely, there's not much use for pain. If, however, the brain perceives it unsafe to move, pain is one way to limit your movement and keep you safe.

Rather than ignoring the whole person in front of me and simply correcting compensation patterns, I grilled her on the time frame surrounding the initial appearance of the pain.

"Are you sure you didn't slip, fall, or get in a car accident?"

"Nope, none of that."

What could shut down the core like this?

I started to think about the diaphragm, breathing, and the role emotion can play in motor control.

"What else was happening in your life in the days leading up to the pain?"

---> Now here's where it gets interesting <---

She sort of looked at me like, “dude WTF does that matter?” for a second, but then proceeded to tell me that she lost her father 20 years ago around this time of year.

He'd suffered a heart attack while cycling.

When she was out for a run she saw a pack of cyclists and it flashed her right back to her father.

I believe this is what caused her core to become inhibited (underworking) and her diaphragm to become facilitated (overworking).

Apparently and understandably, she had some unresolved feelings surrounding his death and she naturally had an emotional response to seeing the cyclists.

When it comes to motor control, our emotional needs are much more important than our need to move. To protect herself emotionally, perhaps her diaphragm tightened. (Just think of how you'd react in a fight/flight situation, perhaps with a gasp?)

Not realizing all of this was happening, she tried to stick to her training plan. But after two lethargic runs (one was a long run) that were “a real struggle”, her hip became painful in run #3.

Not realizing all of this was happening, she tried to stick to her training plan. But after two lethargic runs (one was a long run) that were “a real struggle”, her hip became painful in run #3.

Her body finally spoke loudly enough for her to listen.

After we discussed how all of this may be possible and how difficult it must have been to lose a father suddenly at such a young age, I showed her how to massage her diaphragm and breathe properly.

We practiced breathing for about 5 minutes and then retested her core and hip. About 90% of the muscles were now functional.

After resolving another (much less dramatic, but no less meaningful) compensation involving her knee and hip, I asked her to run up and down the hallway. No pain!

Fast forward to today's follow-up session. It wasn't completely smooth sailing, but in the past week she's been able to resume running consistently again. After today's session I'm confident she's ready to build up even more.

I asked her if she was upset that she wasn't going to run in the half marathon next week which had been her goal race. Given the level of frustration she'd initially expressed during session one, I was sure she must have been feeling down about the whole fall season – you know, the best time to run all year?

I was shocked to hear her response.

She said “you know, I'm actually very happy. In fact, it's been a great fall season.”

I'm thinking, “huh?”

She continued, “I really learned a lot about myself. I don't think many people would have connected the dots like you did, but I really do feel great. Thank you.”

**UPDATE: After implementing the homework from session 2, she's now 100%!